The pc scientists Wealthy Sutton and Andrew Barto have been acknowledged for an extended monitor report of influential concepts with this year’s Turing Award, essentially the most prestigious within the area. Sutton’s 2019 essay “The Bitter Lesson,” as an example, underpins a lot of in the present day’s feverishness round synthetic intelligence (AI).

He argues that strategies to enhance AI that depend on heavy-duty computation slightly than human information are “in the end the simplest, and by a big margin.” That is an concept whose reality has been demonstrated many occasions in AI historical past. But there’s one other essential lesson in that historical past from some 20 years in the past that we should heed.

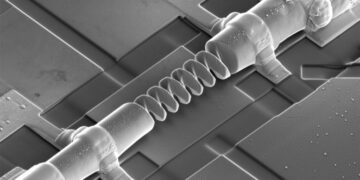

As we speak’s AI chatbots are constructed on massive language fashions (LLMs), that are educated on enormous quantities of knowledge that allow a machine to “motive” by predicting the subsequent phrase in a sentence utilizing chances.

Helpful probabilistic language fashions have been formalized by the American polymath Claude Shannon in 1948, citing precedents from the 1910s and Nineteen Twenties. Language fashions of this kind have been then popularized within the Seventies and Eighties to be used by computer systems in translation and speech recognition, wherein spoken phrases are transformed into textual content.

The primary language mannequin on the size of latest LLMs was published in 2007 and was a part of Google Translate, which had been launched a yr earlier. Skilled on trillions of phrases utilizing over a thousand computer systems, it’s the unmistakeable forebear of in the present day’s LLMs, despite the fact that it was technically completely different.

It relied on chances computed from phrase counts, whereas in the present day’s LLMs are primarily based on what is named transformers. First developed in 2017—additionally initially for translation—these are artificial neural networks that make it attainable for machines to raised exploit the context of every phrase.

The Professionals and Cons of Google Translate

Machine translation (MT) has improved relentlessly previously 20 years, pushed not solely by tech advances but additionally the scale and variety of coaching information units. Whereas Google Translate began by providing translations between simply three languages in 2006—English, Chinese language, and Arabic—in the present day it helps 249. But whereas this may increasingly sound spectacular, it’s nonetheless really lower than 4 % of the world’s estimated 7,000 languages.

Between a handful of these languages, like English and Spanish, translations are sometimes flawless. But even in these languages, the translator sometimes fails on idioms, place names, authorized and technical phrases, and numerous different nuances.

Between many different languages, the service might help you get the gist of a textual content, however often contains serious errors. The most important annual analysis of machine translation methods—which now consists of translations carried out by LLMs that rival these of purpose-built translation methods—bluntly concluded in 2024 that “MT is not solved yet.”

Machine translation is extensively used despite these shortcomings: Way back to 2021, the Google Translate app reached one billion installs. But customers nonetheless seem to know that they need to use such providers cautiously. A 2022 survey of 1,200 individuals discovered that they largely used machine translation in low-stakes settings, like understanding on-line content material exterior of labor or examine. Solely about 2 % of respondents’ translations concerned increased stakes settings, together with interacting with healthcare staff or police.

Positive sufficient, there are excessive dangers related to utilizing machine translations in these settings. Studies have shown that machine-translation errors in healthcare can probably trigger severe hurt, and there are reviews that it has harmed credible asylum cases. It doesn’t assist that customers are inclined to belief machine translations that are easy to understand, even when they’re deceptive.

Realizing the dangers, the interpretation business overwhelmingly relies on human translators in high-stakes settings like worldwide regulation and commerce. But these staff’ marketability has been diminished by the truth that the machines can now do a lot of their work, leaving them to focus extra on assuring high quality.

Many human translators are freelancers in a market mediated by platforms with machine-translation capabilities. It’s irritating to be decreased to wrangling inaccurate output, to not point out the precarity and loneliness endemic to platform work. Translators additionally need to cope with the true or perceived risk that their machine rivals will ultimately exchange them—researchers consult with this as automation anxiety.

Classes for LLMs

The latest unveiling of the Chinese AI model Deepseek, which seems to be near the capabilities of market chief OpenAI’s newest GPT fashions however at a fraction of the value, alerts that very subtle LLMs are on a path to being commoditized. They are going to be deployed by organizations of all sizes at low prices—simply as machine translation is in the present day.

In fact, in the present day’s LLMs go far past machine translation, performing a a lot wider vary of duties. Their basic limitation is information, having exhausted most of what’s obtainable on the web already. For all its scale, their coaching information is more likely to underrepresent most tasks, simply because it underrepresents most languages for machine translation.

Certainly the issue is worse with generative AI. In contrast to with languages, it’s troublesome to know which duties are effectively represented in an LLM. There’ll undoubtedly be efforts to enhance coaching information that make LLMs higher at some underrepresented duties. However the scope of the problem dwarfs that of machine translation.

Tech optimists could pin their hopes on machines having the ability to maintain growing the scale of the coaching information by making their very own artificial variations, or of studying from human suggestions via chatbot interactions. These avenues have already been explored in machine translation, with restricted success.

So the foreseeable future for LLMs is one wherein they’re wonderful at a couple of duties, mediocre in others, and unreliable elsewhere. We’ll use them the place the dangers are low, whereas they might hurt unsuspecting customers in high-risk settings—as has already occurred to laywers who trusted ChatGPT output containing citations to non-existent case regulation.

These LLMs will help human staff in industries with a tradition of high quality assurance, like laptop programming, whereas making the expertise of these staff worse. Plus we should cope with new issues reminiscent of their risk to human artistic works and to the environment. The pressing query: is that this actually the long run we need to construct?

This text is republished from The Conversation underneath a Inventive Commons license. Learn the original article.