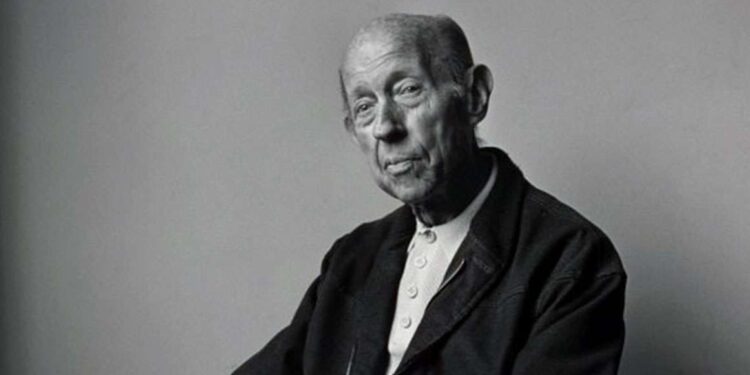

One winter evening in 1924, a 19-year-old named Dorr Legg snuck away to a “charming park,” the place he had his first sexual expertise with one other man, one thing he had been needing—and finding out—for a number of years.

Born in a big house overlooking the campus of the College of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Legg got here from an extended line of Republicans: His household had been energetic within the GOP since its first conference of their state in 1854. Like many Midwestern Republicans, his father deplored Wall Avenue and the fat-cat bankers of the Northeast, even when they largely belonged to his political occasion; he taught his son that prosperity grew out of self-reliance and particular person endeavor, not collusion and backroom deal-making. As for the Democrats, his father added, they ran corrupt machines within the large northern cities and used violence and intimidation to disclaim blacks their rights down south.

An autodidact from a younger age, Legg had been spending time hidden away within the College of Michigan’s library stacks, secretly studying all the pieces he may discover on homosexuality in books of drugs, psychiatry, criminology, witchcraft, and Sigmund Freud. The readings confirmed Legg that he was not alone. Additionally they satisfied him that he was the knowledgeable on his personal situation. When medical medical doctors deemed homosexuals sick and spiritual leaders known as them sinners, Legg shrugged it off.

However the legislation, which counted homosexuals as criminals, was one other matter: The specter of arrest and imprisonment required that homosexuals reside a double life. Typically haughty, at all times confident, Legg resented the truth that he could not reside freely as he happy. As Legg confronted arrest by the police and harassment by the FBI by means of the years, his basic Republican leanings hardened into what one historian known as an impassioned “libertarian mistrust of presidency.” The federal government, he believed, was the gay’s enemy.

***

In 1928, Legg moved to New York Metropolis. He’d simply completed a grasp’s diploma in panorama structure, and he arrived simply in time for the tail finish of town’s growth. The Nice Melancholy meant his design work disappeared, so Legg then discovered employment with the brand new public city planning initiatives within the metropolis and on Lengthy Island. However the Republican in him may by no means convey himself to help the New Deal, even when it had stored him above water.

New York was an electrifying place for homosexuals within the Thirties, and Legg dove proper in. He met like-minded males at Kid’s, a restaurant beneath the Paramount Theater that served as a boisterous and freewheeling gay hangout. Even within the relative freedom New York afforded, he stored tight management of himself, at all times dressing in a conservative swimsuit and tie and sustaining a masculine method. Legg had little persistence for the effeminate and flamboyant “queens” who had been a part of New York’s homosexual underworld. He would not “ship up flares,” as he described the way in which some males signaled to one another, and he detested the “unseemly whoops” some teams of homosexuals brashly made as they paraded down the streets. He apprehensive that their shenanigans and gender-subversive behaviors risked detection by legislation enforcement.

These considerations did not preserve him from attending a handful of drag balls in Harlem, the place he met a number of black pals and lovers. Their accounts of the bias and discrimination they skilled gave Legg new perception into his personal situation. “I too was a member of a stigmatized group,” he realized.

Legg’s cautious self-presentation was not sufficient to maintain the eyes of the legislation off him. When he returned to Michigan within the mid-Forties to look after his ailing father and handle the household enterprise, his public outings with enticing black males drew police consideration. The Detroit cops started surveilling Legg, and so they lastly arrested him on a cost of “gross indecency” two years after Legg’s father died in 1947. Legg the libertarian was outraged that the police would spy on a law-abiding citizen and was livid that the federal government would intrude in his personal life. “Didn’t the ‘Do not tread on me,’ of the rattlesnake flag,” he fumed, “imply something anymore?”

When the information of his arrest obtained out, Legg’s church suspended him and his landlord threatened to kick him out. Legg did not wait round to see what else was coming. He packed his baggage for Los Angeles, becoming a member of a whole lot of 1000’s of People who had been transferring into Southern California for the earlier 20 years, drawn by its low cost land and plentiful jobs. Like a lot of his fellow transplants, Legg regarded to California as a spot the place rugged individualism may flourish. He hoped Los Angeles’ tolerant and relaxed fame meant he can be left alone—by the cops, anyway.

After 1945, L.A.’s already giant gay inhabitants ballooned as 1000’s of returning homosexual servicemen and ladies determined to remain of their port of entry, simply as others did farther north in San Francisco. But Los Angeles’ homosexual growth coincided with the federal authorities’s crackdown on homosexuals, and Legg quickly discovered that Los Angeles wasn’t all that totally different from Detroit. Nowhere was within the Nineteen Fifties. L.A.’s new chief of police, “Wild Invoice” Parker, directed his division to “clear up” town’s bustling streets. The police division’s head legal psychiatrist offered medical justification for rounding up homosexuals: They had been pathological degenerates, he argued, who preyed on anybody, particularly kids. Los Angeles’ police division shortly racked up an inventory of 10,000 “intercourse offenders,” made up virtually completely of the gay women and men who had been arrested throughout raids of homosexual bars and public parks and even whereas simply strolling down the road. L.A.’s politicians joined within the assault, passing legal guidelines meant to close down the bars, eating places, and different institutions the place homosexuals gathered.

California’s Supreme Courtroom would strike down a number of of the legal guidelines—on the grounds that the companies ought to be capable of function, not as an endorsement of homosexuals’ proper to congregate. Both approach, town’s sturdy anti-gay regime had its supposed chilling impact, driving homosexual women and men even additional underground.

On the federal stage, each main political events elevated the federal government’s energy to focus on homosexuals. In 1950, Harry Truman’s Democratic administration started rooting out suspected homosexuals from the federal authorities. Three years later, Republicans upped the ante: President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued Govt Order 10450, which banned homosexuals from working within the federal authorities, formally codifying the witch hunt into legislation.

But even on this oppressive period, a handful of homosexuals started planting seeds of resistance that might ultimately develop into homosexual liberation. They known as their trigger the “homophile motion,” a time period consciously chosen to emphasise the “love of fellow man”; they felt that society used “gay” to focus consideration on the sexual acts it condemned. These leaders of the early homophile motion got here from assorted walks of life and held political philosophies that ranged from libertarianism to communism.

***

A 12 months after arriving in L.A., the place he continued to work as a panorama architect, Legg joined Merton Hen, a black accountant, in creating the Knights of the Clock, a company that offered counseling, social service help, and authorized help to interracial homosexual {couples}. Across the identical time, Legg grew to become one of many first members of the Mattachine Society, broadly thought-about the primary homophile group in the USA.

Based by Harry Hay, a labor activist and Communist Celebration member who had grown up in a rich, conservative Republican household, the Mattachine Society operated as a gay secret society modeled on the Communist Celebration’s cell construction, a system that organized members into small teams that remained separated to attenuate the danger of a police raid blowing the lid off the entire clandestine operation. Everybody additionally used made-up names. Legg had no use for Mattachine’s Communist management—he “discovered Marxism fully absurd, a ponderously foolish utopianism”—however he did not assume it was value worrying an excessive amount of about. Because it grew, the group quickly had extra non-Communists than reds, together with a quantity who recognized as conservative or libertarian, similar to Dale Jennings, a younger author from Colorado.

Mattachine conferences targeted on discussing homosexuals’ civil rights. Not everybody wished simply to speak. In October 1952, Legg hosted a Mattachine assembly at his house. The evening’s visitor speaker was a former member of the Los Angeles Police Division vice squad who had just lately stop his job in protest over the underhanded ways his unit used to lure homosexuals into arrest. The methods, he defined, included hiring particularly good-looking males, usually aspiring Hollywood actors, to entrap homosexuals in parks, public restrooms, and bars. For many of the 75 women and men in attendance, together with Legg, nothing in regards to the officer’s discuss got here as a shock. Earlier that 12 months, Jennings had been arrested after making an attempt to disregard a suspicious man trailing him on his stroll house who then pressured his approach into Jennings’ house. There, whilst Jennings continued to withstand his advances, the person shoved Jennings’ palms down his pants earlier than flashing him his police badge. Even of their properties, homosexuals could not discover sanctuary from the legislation.

Nonetheless, it was one thing else to listen to straight from the horse’s mouth how coordinated and even corrupt the police had been of their efforts to incriminate homosexuals. The usually civilized Mattachine dialogue group become a yelling match, all of the pent-up frustrations and anger erupting into cacophony. Nobody may hear a phrase at first. Finally, it grew to become clear that half of the attendees wished to maintain speaking about what that they had simply discovered and the remainder wished to do one thing about it. This second group, led by Legg and Jennings, moved to Legg’s kitchen. They had been joined by Martin Block, a New Yorker who owned a neighborhood bookstore and who had already been near his breaking level with the Mattachine Society for “each one in every of their Communist enthusiasms.” The time lastly felt proper for a break up.

Somebody proposed forming a separate group. Another person proposed beginning {a magazine}. They opted to do each.

They known as the brand new group ONE, Inc. The title had been impressed by a citation from the thinker Thomas Carlyle: “A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all males one.” The “Inc.” denoted their registration as an organization, however it was additionally a deliberate transfer to sign that the group had no connections to communism. ONE would go on to host lectures and dialogue teams and to fund analysis research on homosexuality. It launched ONE Journal in January 1953, three months after the group’s founding. The journal was the very first publication in the USA dedicated to optimistic protection of homosexuality.

Legg stop his profitable profession to work full time as ONE Journal‘s enterprise supervisor and assistant editor. The job paid a paltry $25 every week, however he felt compelled by this new mission. “The straightforward reality,” he wrote, “was that my occupation not got here first. The minority with which I used to be more and more figuring out myself was quickly buying the character of an crucial obligation.”

Legg approached his work with the entrepreneurial spirit his father had instilled in him. He drove throughout Los Angeles promoting the journal to newsstands and traveled to homophile teams across the West Coast to advertise the publication. Inside a 12 months, ONE Journal had greater than 5,000 subscribers across the nation—and a a lot bigger readership, because the copies obtained quietly handed round.

On the masthead, Legg glided by William Lambert. It wasn’t precisely a pseudonym: extra a variation of his full title, William Dorr Lambert Legg. Below different bylines—Marvin Cutler, Hollister Barnes, W. G. Hamilton, Valentine Richardson, Sidney Rothman—Legg penned articles to fill its pages. Typically he wrote as Wendy Lane, because the journal could not get many lesbians to write down for it at first. Though Legg used pseudonyms to maintain from being detected by authorized authorities, the faux names had an additional benefit: They stored his readers from realizing how few writers truly contributed to ONE Journal in its early years.

The journal debuted because the U.S. Publish Workplace, just like the FBI and native police, was clamping down on homosexuals. It tracked males who subscribed to physique magazines, the place muscular male fashions posed carrying virtually nothing. Investigators generally participated in pen-pal golf equipment, the place they fashioned connections with males they suspected of being gay after which surveilled their mail to find out who of their correspondence may also be homosexual. Practically two-thirds of ONE‘s subscribers shelled out an extra greenback above the annual $2 subscription worth to have their copies despatched in a plain, sealed envelope with nothing indicating its origins. However a homophile journal had little likelihood of going undiscovered. If homosexuals weren’t shielded from having vice squads barge proper into their properties, there was no approach their mail wasn’t going to get opened too.

The Comstock Act of 1873, nonetheless in impact, made it unlawful to mail something lascivious, lewd, or obscene, and ONE‘s protection of homosexuality put it in fixed jeopardy of being mentioned to violate the legislation. The Los Angeles publish workplace refused to mail the August 1953 subject on account of its cowl title: “Gay Marriage?”

Legg wasn’t going to let the federal government intimidate his journal into silence. He employed a younger lawyer, Eric Julber, who began hounding the Postal Service. After three weeks, the publish workplace lastly launched the difficulty when the solicitor basic in Washington, D.C., declared it wasn’t obscene. On the journal’s subsequent subject, Legg intentionally poked on the authorities with the headline “ONE Is Not Grateful.” A canopy observe elaborated on Legg’s anger. “Your August subject was late,” it learn, “as a result of the postal authorities in Washington and Los Angeles had it underneath a microscope.”

Los Angeles’ postmaster made his subsequent transfer when he declared that the October 1954 subject included “obscene, lewd, lascivious, and filthy” content material and ordered that every one the copies be stored from distribution. Legg instructed Julber to sue. Recognizing the case would hinge on whether or not the journal’s First Modification rights had been violated, Julber requested the American Civil Liberties Union’s L.A. workplace for assist. However the group wasn’t serious about a case involving homosexuals.

Native legislation enforcement recurrently got here to ONE‘s shabby workplaces in downtown Los Angeles. In 1956, the FBI confirmed up too. The bureau’s director, J. Edgar Hoover, was irate over an article that recommended its high officers had been homosexuals. For greater than a decade, rumors had swirled that Hoover was carrying on an affair together with his right-hand man, Clyde Tolson. Incensed, Hoover fired off an offended observe to Tolson: “We have got to get these bastards.” A day later, FBI brokers had been pounding at ONE‘s workplace door.

Their terrifying presence solely strengthened Legg’s conviction that the federal government had an excessive amount of energy over the lives of everybody, particularly homosexuals. Gathering his nerve and his unwavering perception that he did not should reply to anybody, Legg ignored the brokers’ questions and ordered them out. “I am not going to present you any data,” Legg declared. “What are your names and numbers? That is all I am serious about.”

In the meantime, ONE‘s court docket case dragged on. Initially, each a district court docket and a court docket of appeals sided with the postmaster. However the appeals ruling offered a gap when, citing an article within the confiscated October subject titled “Sappho Remembered,” it dominated the journal was “low cost pornography calculated to advertise lesbianism.” ONE‘s lawyer took this language straight to the Supreme Courtroom, asking whether or not merely being a optimistic portrayal of homosexuality was sufficient to make a textual content obscene, and due to this fact not coated by the First Modification. Up till then, the Courtroom had by no means even thought-about a case regarding homosexuality, and it discovered this assertion so novel that, even with out listening to oral arguments, it unanimously reversed the decrease courts’ rulings.

The Supreme Courtroom issued no written opinion, and The New York Instances gave just one sentence to the case about “{a magazine} coping with homosexuality.” However Legg and his colleagues knew that they had gained a landmark determination in ONE, Inc. v. Olesen (1958). The nation’s highest authorized authority had cleared the way in which for ONE and the 2 different homophile publications, Mattachine Overview and The Ladder, to freely function—the primary nationwide victory for the fledgling motion. Legg additionally took pleasure in realizing that he had helped push again an overbearing, invasive authorities. “We took on the entire federal authorities for a interval of 4 years,” Legg enthused, “and so they spent large cash, with high attorneys from Washington, to squash us. They usually did not! We gained.”

***

Eight months later, Legg wrote an article for ONE titled “I Am Glad I Am Gay.” It voiced his frustration that the majority homosexuals continued to see their homosexuality as inherently flawed, an angle that led them to reside secret lives of disgrace whereas accepting society’s judgments of them as sick, sinful, and legal. Whereas the truth that Legg had written the piece underneath a pseudonym indicated he nonetheless was taking steps to hide his personal identification, the article additionally confirmed he had little persistence with homophile organizations who felt they “ought to cooperate to the fullest extent with ‘public authorities.'” As an alternative, Legg counted himself among the many small group of “admitted homosexuals” who “are actively, resiliently pleased with their homosexuality, glad for it.” These homosexuals believed they need to have “the identical authorized and social privileges as others, no extra, but in addition, no much less.”

Though ONE, Inc. had been created as a breakaway group from the Mattachine Society, it continued to work intently with Mattachine and with the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), a lesbian group out of San Francisco. “We needed to stand shoulder to shoulder as a result of the motion was so small,” Legg has defined. However by 1958, the unfastened bonds that related the small homophile motion had been starting to fray. The irony was that it was Legg the Republican, and never the widely extra left-leaning members of the DOB and Mattachine, who insisted that homosexuals had been a minority group deserving of equal standing underneath the legislation.

Legg’s view that homosexuals ought to be capable of reside free of presidency interference additionally put him in battle together with his personal political occasion within the Nineteen Fifties. Republicans in Washington, similar to Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy, had grow to be wanting to root out homosexuals who labored for the federal government and to curtail the civil liberties of homosexual women and men in every single place. Legg detested McCarthy. “True conservatives,” he would say, “are libertarians. They consider in limiting the hand of presidency.”

Legg thought the homophile motion ought to spell out homosexuals’ fundamental civil liberties, amongst them the suitable to be free of presidency surveillance and discriminatory legal guidelines. He recommended that the 1961 ONE Midwinter Institute, an annual convening of the three homophile teams, could possibly be targeted on outlining a “Gay Invoice of Rights.” Legg did not think about any of this as controversial, no less than not amongst homophile activists. Certainly, what he was advocating was an early instance of the identification politics that homosexual liberationists would heartily embrace greater than a decade later.

However in 1961, Legg’s proposal was nearly lifeless on arrival, due to disagreements over politics and political technique. An early planning assembly for the convention virtually fell aside when nobody may agree over what phrases like “liberty, rights, freedom, [and] free-will” even meant, the very phrases that had been Legg’s guiding ideas all his life. Within the DOB’s journal The Ladder, Del Martin argued that publishing a invoice of rights would generate a backlash that was “prone to set the homophile motion again into oblivion” by making political calls for that might by no means be granted. When the 1961 Midwinter Institute lastly did meet, Jaye Bell, the DOB’s president, delivered a crushing blow on the banquet occasion. A Gay Invoice of Rights, she advised the gathering, would “be probably a particularly harmful act to the work which has been carried out and is being carried out to vary public opinion.” Bell burdened a gradual method of steady schooling to vary widespread perceptions about homosexuals, fairly than the novel act of demanding rights. “Both these are rights we have already got, or they’re rights which can’t be requested, as a result of to take action can be to demand that folks have the attitudes we prescribe for them,” she argued. “One can not demand or legislate attitudes.”

There can be no Gay Invoice of Rights. Legg was livid, lashing out at “brain-washed” lesbians who, “by advantage of their very own rare private contact with the brutal realities of the denial of rights the male gay so repeatedly experiences, had been however a small step forward of heterosexuals of their comprehensions of what the issues are.”

Legg’s feedback betrayed each an ignorance of and an indifference to lesbian considerations: In truth, police raided lesbian bars on a regular basis. However lesbians did not often cruise within the ways in which homosexual males did, and that made them much less susceptible to the practices by which legislation enforcement recurrently surveilled and entrapped gay males, which Legg had skilled.

An editorial doubtless written by Legg and Don Slater, the pinnacle editor of ONE and likewise a Republican, expressed dismay that almost all who had opposed the Gay Invoice of Rights had acted as if “the lot of the gay just isn’t so dangerous in spite of everything.” It was the view of ONE, however, that the gay was a “second-class citizen” who required the “safeguarding of particular person liberty from [the] tyranny of the bulk.”

The language of private freedom signaled Legg’s libertarian views. His demand for motion marked him as a militant. These had been reinforcing fairly than contradictory positions, originating collectively from Legg’s agency conviction that authorities’s powers needed to be restrained to ensure that anybody, particularly the gay, to have actual freedom. These politics and that temperament made him an outlier within the homophile motion.

For a decade, that hadn’t mattered a lot. However the fallout over the Gay Invoice of Rights—ONE and the DOB would have little connection going ahead, and issues with Mattachine additionally grew more and more strained—foreshadowed the alienation Legg would quickly really feel. In a short while, the rising successes of the New Left and the Civil Rights Motion led leaders of the DOB, Mattachine, and a brand new umbrella group, the East Coast Homophile Organizations, to vary their ways. The as soon as apolitical motion grew to become politically energetic, even going as far as to make use of public demonstrations to protest discrimination, and now spoke within the language of minority rights by the mid-Sixties. From there it grew into the decidedly left-leaning homosexual rights motion of the Nineteen Seventies.

In the meantime, one other group of homosexual males and lesbians began founding what they known as “homosexual Republican golf equipment” to make their presence recognized to the GOP. In 1977, Legg grew to become one in every of them, as a founding member of the Lincoln Republicans of Southern California. The group would quickly rename itself the Log Cabin Membership. By the mid-Nineteen Eighties, the Los Angeles group can be the biggest and strongest homosexual Republican membership within the nation. Within the early Nineteen Nineties, it linked up with different homosexual Republican teams to kind the nationwide Log Cabin Republicans group.

Legg would grumble in regards to the “1969ing [of] all the pieces.” By this he meant how so many noticed that 12 months’s Stonewall Insurrection because the second that launched the homosexual rights motion, failing to acknowledge the “twenty years earlier than [of] a hell of a whole lot of onerous work by a whole lot and a whole lot of devoted individuals who put their lives and their jobs and all the pieces else on the road.” A few of this was simply the comprehensible response of a cantankerous man in his 70s irritated by youthful generations who did not know or admire the dangers and sacrifices that had led to their second. Nevertheless it additionally mirrored Legg’s opposition to the place the homosexual rights motion was going because it aligned with the problems and organizations of the left.

Not that he was all that pleased with the place his Republican Celebration appeared headed both. One other group of Republicans was placing the GOP on a collision course with the likes of Legg, and with any homosexual Republicans who believed that their occasion stood for restricted authorities, private privateness, and the liberty to reside their lives as they noticed match.

This text has been tailored from Coming Out Republican: A History of the Gay Right by permission of The College of Chicago Press.