On a wooded hill edged by rice fields in Sri Lanka’s northern Mullaitivu district sit the ruins of an historical Buddhist monastery. Members of the nation’s Sinhalese majority name it “Kurundi Viharaya”. For Tamils, who’re principally Hindus and contemplate the war-battered north their homeland, it’s “Kurunthoor Malai”. Since 2018, when the state archaeological division started excavating the positioning, Tamil and Sinhalese nationalists have rowed over which group has a higher declare to it.

Sri Lanka’s lengthy civil battle, between the secessionist Tamil Tiger rebels and the Sinhalese-dominated authorities, has left deep scars in Mullaitivu. Tens of hundreds of Tamil civilians have been slaughtered by the military there in 2009 throughout the battle’s horrible denouement, based on the UN. Some locals who fled the combating have been solely permitted to return in 2013. It was round then that the division began displaying curiosity within the many archaeological websites, together with Kurundi, dotted throughout the vanquished Tigers’ former area.

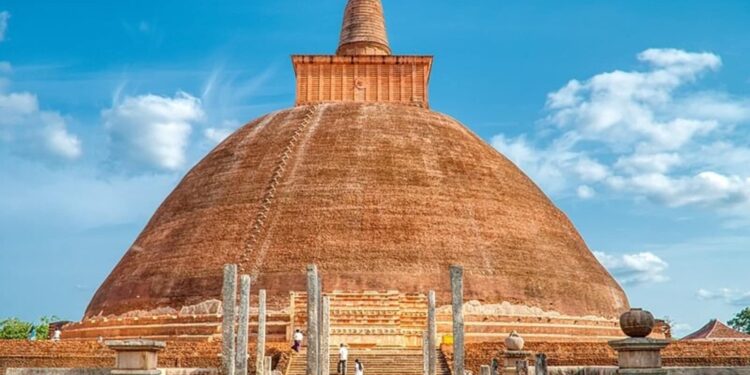

The Kurundi advanced dates again to the 2nd century BC, with extensions added over subsequent centuries. The restricted space that has been excavated features a stupa, or Buddhist reliquary tower, and a picture home, used to show representations of the Buddha. On the positioning’s summit, white butterflies flit to a chatter of cicadas.

For Sinhalese nationalists similar to Ellawala Medhananda, a Buddhist monk and writer of a well-liked e book on the Buddhist heritage of Sri Lanka’s north and east, such ruins serve a eager political function. On the coronary heart of the declare for a Tamil homeland is a perception that ethnic Tamils have been the unique settlers of Sri Lanka’s north and east. For Sinhala nationalists, the traditional Buddhist websites repudiate that declare.

Tamil nationalists counter that the monuments have been additionally Hindu. The 2 religions usually co-existed in pre-modern Sri Lanka. Excavations at many Buddhist monuments in northern Sri Lanka have revealed proof of Hindu apply. Even the place excavations are restricted at a website, native Hindus usually lay declare to it. Kurundi is domestically believed to comprise a Hindu temple; Hindus have begun gathering to hope there. These rival claims have put archaeology on the entrance line of Sri Lanka’s communal fissure. It has turn into a “extremely unstable ethnic subject” that has “created a pressure within the minds of each Sinhalese and Tamils due to its political implications”, writes G. P. V. Somaratna, a historian.

The Kurundi website was protected by British directors in 1933. Earlier this 12 months, the archaeological division—citing proof of unexplored ruins outdoors its 78-acre expanse—referred to as for an extra 229 acres, together with fertile paddy fields, to be blocked off. This has outraged the Tamil farmers who domesticate the land. Tamil leaders decry the proposal as an effort to “Sinhalise” the area. The positioning has been decked in signage, written in Sinhalese, that doesn’t point out its Hindu significance. Native Hindus have filed lawsuits to forestall additional adjustments. A choose who dominated of their favour fled the nation in August, citing loss of life threats and “a variety of stress”.

The politics of the dispute are warping historical past. It’s not merely the case that Tamils and Sinhalese as soon as worshipped facet by facet. Buddhist and Hindu identities have been additionally extra fluid than Sri Lanka’s bitter politics in the present day permits; some ethnic Tamils have been as soon as Buddhist. That most likely makes the traditional websites no less than as Tamil as they’re Sinhalese—even when not in a manner that extremists on both facet would recognise. The row is about ethnicity, not faith, and primarily about “who acquired right here first”, observes Shamara Wettimuny, a historian.

A rising variety of sacred websites are seeing the identical ethnic disagreement. Kandarodai, a group of restored stupas within the northernmost Jaffna Peninsula, has been fenced off and put in (principally Sinhalese) military palms. Native Hindus are outraged. Rowdy protests at another monuments have led to police intervention. And with an election due subsequent 12 months, such tensions are prone to improve. A Tamil human rights lawyer calls this “sectarian battle primarily based on ruins”.

© 2023, The Economist Newspaper Restricted. All rights reserved. From The Economist, revealed underneath licence. The unique content material will be discovered on www.economist.com

On a wooded hill edged by rice fields in Sri Lanka’s northern Mullaitivu district sit the ruins of an historical Buddhist monastery. Members of the nation’s Sinhalese majority name it “Kurundi Viharaya”. For Tamils, who’re principally Hindus and contemplate the war-battered north their homeland, it’s “Kurunthoor Malai”. Since 2018, when the state archaeological division started excavating the positioning, Tamil and Sinhalese nationalists have rowed over which group has a higher declare to it.

Sri Lanka’s lengthy civil battle, between the secessionist Tamil Tiger rebels and the Sinhalese-dominated authorities, has left deep scars in Mullaitivu. Tens of hundreds of Tamil civilians have been slaughtered by the military there in 2009 throughout the battle’s horrible denouement, based on the UN. Some locals who fled the combating have been solely permitted to return in 2013. It was round then that the division began displaying curiosity within the many archaeological websites, together with Kurundi, dotted throughout the vanquished Tigers’ former area.

The Kurundi advanced dates again to the 2nd century BC, with extensions added over subsequent centuries. The restricted space that has been excavated features a stupa, or Buddhist reliquary tower, and a picture home, used to show representations of the Buddha. On the positioning’s summit, white butterflies flit to a chatter of cicadas.

For Sinhalese nationalists similar to Ellawala Medhananda, a Buddhist monk and writer of a well-liked e book on the Buddhist heritage of Sri Lanka’s north and east, such ruins serve a eager political function. On the coronary heart of the declare for a Tamil homeland is a perception that ethnic Tamils have been the unique settlers of Sri Lanka’s north and east. For Sinhala nationalists, the traditional Buddhist websites repudiate that declare.

Tamil nationalists counter that the monuments have been additionally Hindu. The 2 religions usually co-existed in pre-modern Sri Lanka. Excavations at many Buddhist monuments in northern Sri Lanka have revealed proof of Hindu apply. Even the place excavations are restricted at a website, native Hindus usually lay declare to it. Kurundi is domestically believed to comprise a Hindu temple; Hindus have begun gathering to hope there. These rival claims have put archaeology on the entrance line of Sri Lanka’s communal fissure. It has turn into a “extremely unstable ethnic subject” that has “created a pressure within the minds of each Sinhalese and Tamils due to its political implications”, writes G. P. V. Somaratna, a historian.

The Kurundi website was protected by British directors in 1933. Earlier this 12 months, the archaeological division—citing proof of unexplored ruins outdoors its 78-acre expanse—referred to as for an extra 229 acres, together with fertile paddy fields, to be blocked off. This has outraged the Tamil farmers who domesticate the land. Tamil leaders decry the proposal as an effort to “Sinhalise” the area. The positioning has been decked in signage, written in Sinhalese, that doesn’t point out its Hindu significance. Native Hindus have filed lawsuits to forestall additional adjustments. A choose who dominated of their favour fled the nation in August, citing loss of life threats and “a variety of stress”.

The politics of the dispute are warping historical past. It’s not merely the case that Tamils and Sinhalese as soon as worshipped facet by facet. Buddhist and Hindu identities have been additionally extra fluid than Sri Lanka’s bitter politics in the present day permits; some ethnic Tamils have been as soon as Buddhist. That most likely makes the traditional websites no less than as Tamil as they’re Sinhalese—even when not in a manner that extremists on both facet would recognise. The row is about ethnicity, not faith, and primarily about “who acquired right here first”, observes Shamara Wettimuny, a historian.

A rising variety of sacred websites are seeing the identical ethnic disagreement. Kandarodai, a group of restored stupas within the northernmost Jaffna Peninsula, has been fenced off and put in (principally Sinhalese) military palms. Native Hindus are outraged. Rowdy protests at another monuments have led to police intervention. And with an election due subsequent 12 months, such tensions are prone to improve. A Tamil human rights lawyer calls this “sectarian battle primarily based on ruins”.

© 2023, The Economist Newspaper Restricted. All rights reserved. From The Economist, revealed underneath licence. The unique content material will be discovered on www.economist.com